Revisiting the devaluation debate

The debate on taka devaluation is a debate on whether the exchange rate is currently overvalued. How do we know?

There are three common reference exchange rates often considered. The exchange rate may be overvalued with respect to purchasing power parity (PPP) or relative to the rate assumed needed to balance the current account (CA). The third is the persistent excess of the informal market rate over the interbank market rate.

Overvaluation of an exchange rate for any of the three reasons (PPP or current account balance or informal market premium) is something that happens. The key question is what it means when such overvaluation happens.

The PPP exchange rate is the rate that equalises the cost of a market basket of goods between two countries. For instance, if the cost of a representative basket of tradable goods is $50 in the US and Tk 4,700 in Bangladesh, then the PPP exchange rate is Tk 94 per dollar.

The taka is overvalued with respect to the US dollar if the exchange rate is below the PPP exchange rate.

The second way to gauge overvaluation is in comparison to an exchange rate presumed necessary to induce balanced trade or the current account. Since such an exchange is not even indirectly observable, persistent trade deficit at the prevailing exchange rate is assumed to indicate overvaluation.

In a floating exchange rate system where the market is allowed complete free play, it is hard to argue that the exchange rate has the “wrong” value since competition in the market will always equalise supply and demand.

The “correct” value for the exchange rate is not the one that satisfy PPP or generate trade balance but rather whatever rate currently prevails without any central bank intervention.

De jure, we have a floating exchange rate but de facto it is managed by the Bangladesh Bank through directives as well as buying and selling the dollar.

Under such a regime, overvaluation occurs when the exchange rate is lower than the rate such that the BB either has to sell dollar or direct the authorised dealers to keep the rate at a prescribed level.

Is taka currently overvalued according to these metrics?

According to the BB’s Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) -- a measure of the value of taka against a trade weighted average of currencies of our key trading partners adjusted for differences in inflation -- the level of the nominal taka-dollar rate consistent with keeping the REER constant at its 2015/16 level has varied between Tk 93-94 of late, compared with the interbank average rate of Tk 84.9/dollar.

This suggests an overvaluation of about Tk 10 per dollar owing to the failure of the nominal taka-dollar rate to rise in line with the differential between inflation in Bangladesh with inflation in our trading partners since 2015/16.

As a result, the prices of all identical goods in Bangladesh relative to their prices in our trading partners has increased by Tk 10 on average since 2015/16.

The trade deficit has risen from $7 billion in fiscal 2012-13 to $15.5 billion in fiscal 2018-19. Deficit in the services account during the same period increased from $3.1 billion to $3.7 billion.

Thanks to remittances, the current account was in surplus until fiscal 2015-16. But it turned into deficit, reaching as high as $9.6 billion in fiscal 2017-18, because of a sharp drop in remittances and declined to $5.2 billion in fiscal 2018-19 as remittances recovered considerably.

Surplus in the financial account reinforced the current account surplus to produce large surpluses in the overall balance of payments until fiscal 2016-17.

The BB accumulated foreign exchange reserves rapidly, suggesting undervaluation until fiscal 2016-17 despite an imbalance in merchandise and services trade.

Remittances, aid flows and private foreign borrowing augmented the supply of foreign exchange to create an excess supply that needed to be siphoned off to prevent taka appreciation. This changed since fiscal 2016-17.

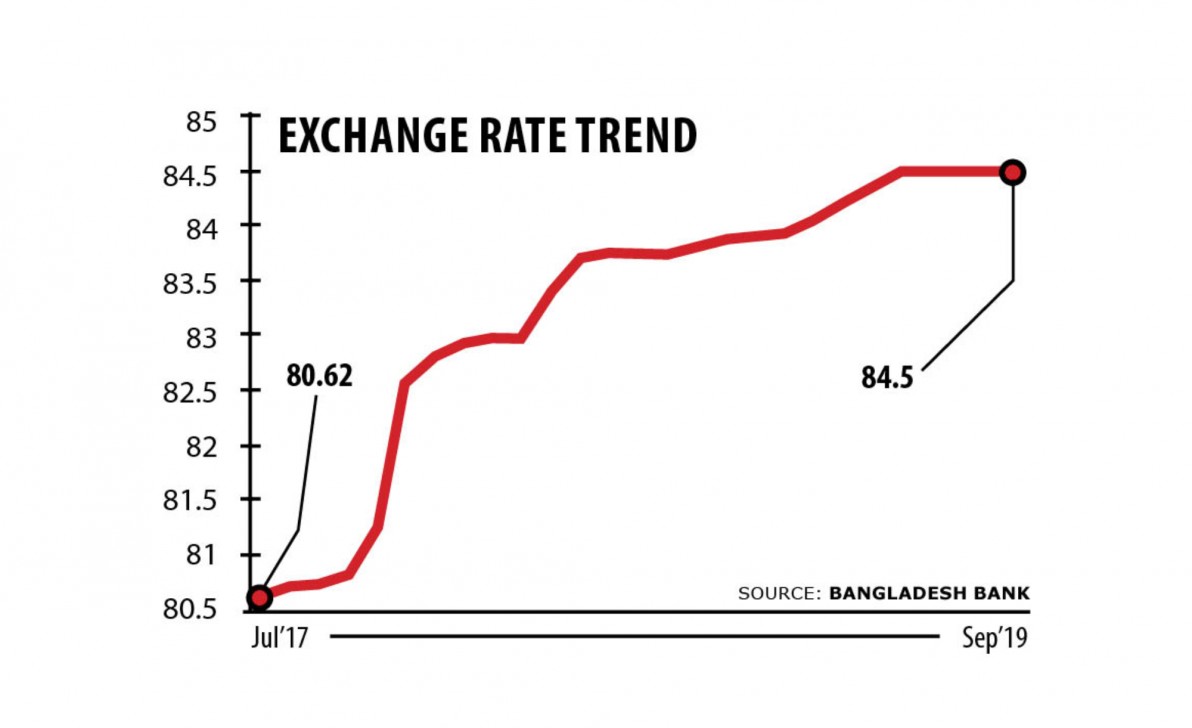

BB sold more than $4.6 billion in fiscal 2017-18 and fiscal 2018-19 and another $423 million so far in fiscal 2019-20 to keep the exchange rate from depreciating too much.

Gross official reserves in months of import cover has declined from its peak of 8 in fiscal 2016-17 to 6 in fiscal 2018-19.

The central bank limits the rates at which authorised dealers can sell foreign exchange and attempts to ensure compliance by imposing penalties.

Such directed exchange rates often induce recalibration of foreign currency contracts and misreporting by banks. It can also divert foreign currency trades to the unofficial market.

An indication of divergence between the directed rate and the market rate is the wedge between the officially reported interbank exchange rate and the unofficial market rate.

Large injections of dollar liquidity in fiscal 2017-18 and fiscal 2018-19 reduced the wedge to less than one taka per dollar. With somewhat restrained interventions and large trade and services deficits in fiscal 2019-20 so far, the wedge between the two rates has increased to Tk 2.6 per dollar.

The above suggests taka is overvalued certainly in PPP terms as well as being below the market clearing level.

Persistence of external trade deficit also suggests overvaluation, but this is not as much of a certainty because it is extremely hard to figure how much.

Many different factors on both the trade and the financial sides influence a country’s trade imbalance besides just the exchange rate.

The exchange rate that balances trade depends on the values taken by all these other factors. There isn’t one exchange rate value that will balance trade. Yet, many observers still contend that a country needs to devalue currency by some percentage to eliminate a trade deficit.

The most pertinent question then is what the risks are in keeping the value of taka where it is ignoring the whole gamut of evidence suggesting that it is significantly overvalued.

Note that the BB pursues an implicit target rate, something that used to be explicit when we were under a fixed rate system prior to May 3, 2003. When overvalued, this target needs a correction. Such a correction can be called devaluation, except that it is not intended to undervalue the exchange rate to gain competitive advantage against external competitors.

The latter is akin to currency manipulation through prolonged foreign exchange intervention or the use of laws or regulations to keep a country’s currency undervalued to gain a trade advantage. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) Articles of Agreement prohibits these tactics, although it has no enforcement mechanism.

Why is a correction warranted? There are many channels through which an exchange rate overvaluation affects trade.

It discriminates against exports by reducing the ability of exporters to compete in foreign markets. Import-competing industries face increased pressure from foreign goods, resulting in increased calls for protection against imports from industrial and agricultural lobbies.

Exporters lobby for cash subsidies and tax waivers to make up what they are losing on the exchange rate. The adverse impact on export and the import competing sectors impede growth since it is in these sectors that productivity advances are often most rapid.

Governments yield to lobbying incurring large fiscal costs. Overvaluation can also induce capital flight if investors start anticipating a devaluation.

Interventions to defend an overvalued exchange rate drains liquidity in the domestic money market, thus exerting upward pressure on the interest rates.

A correction of the target will serve the dual purpose of uniformly increasing the incentives to exporters and protecting import competing industries while allowing monetary policy to focus on managing domestic liquidity and assuaging anticipated devaluation induced capital flight.

Additionally, the correction will strengthen the incentive to remit, thus reinforcing the impact of goods and services trade deficit contraction on the current account balance.

Consequently, it will obviate the need for borrowing to finance the overvaluation induced deficit in merchandise and services trade.

The correction will increase the cost of imports, unless the import duties are adjusted in the opposite direction. It will also increase the local currency cost of servicing external debt.

But, as the joint World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis in June 2019 showed, the debt service-to-revenue ratio remains on a declining trend and below its threshold even with a one-time large currency devaluation shock.