Brain area responsible for pessimism found

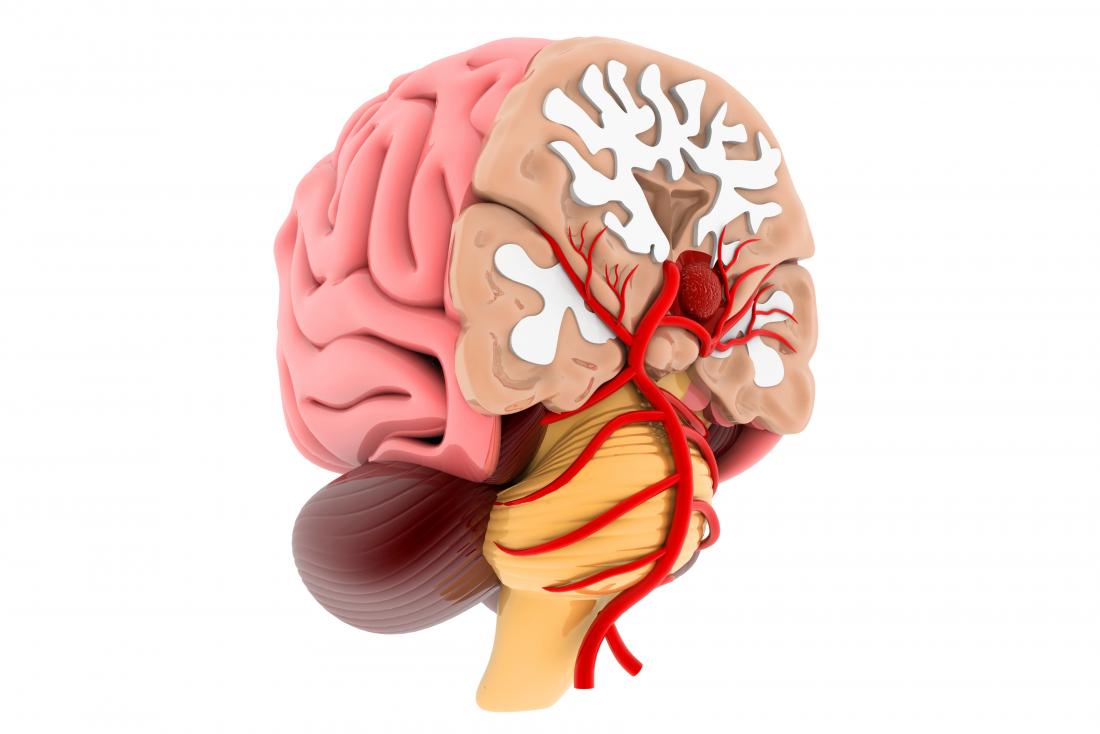

Neuroscientists have now found the brain area responsible for pessimism. The new research suggests that both anxiety and depression are caused by an overstimulation of the caudate nucleus.

Looking at mice, our fellow mammals, can offer important insights into human behavior.

A new study, published in the journal Neuron, examines the neurological underpinnings of pessimism in mice and also finds clues about anxiety and depression in humans.

The new research was led by senior researcher Ann Graybiel, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Prof. Graybiel and colleagues focused on a type of decision-making process known as approach-avoidance conflict.

Approach-avoidance conflict describes situations in which people (or mammals) have to decide between two options by weighing the positive and negative aspects of each alternative.

Previous research that Prof. Graybiel conducted with her team found the brain circuits responsible for this kind of decision-making. They then found that having to decide in this scenario can induce significant stress, and that chronic stress makes rodents choose the riskier option that has the highest potential reward.

The caudate nucleus and decision-making

In the new study, to recreate the scenario in which rodents have to choose by weighing positives and negatives, the scientists offered mice a squirt of juice as a reward but coupled it with an aversive stimulus: a puff of air in the face.

Over several trials, the researchers varied the ratio of reward to unpleasant stimuli and gave the rodents the ability to choose whether to accept the reward with the aversive stimulus or not.

As the researchers explain, this model requires that the rodents perform a cost-benefit analysis. If the reward of juice weighs more than the unpleasant sensation, the rodents will choose it, but if one squirt of juice comes with too many puffs of air, they won't.

They also gave a small electric shock to the rodents' caudate nucleus to see how it affected their decision-making. When this area was stimulated, the rodents did not make the same decisions as they had before receiving a stimulus.

Specifically, the rodents focused much more on the cost of the unpleasant stimulus than they did on the value of the reward. "This state we've mimicked has an overestimation of cost relative to benefit," explains Prof. Graybiel.

Also, the scientists found that stimulation of the caudate nucleus led to a change in the rodents' brainwave activity.