Biden's chip dreams face reality check of supply chain complexity

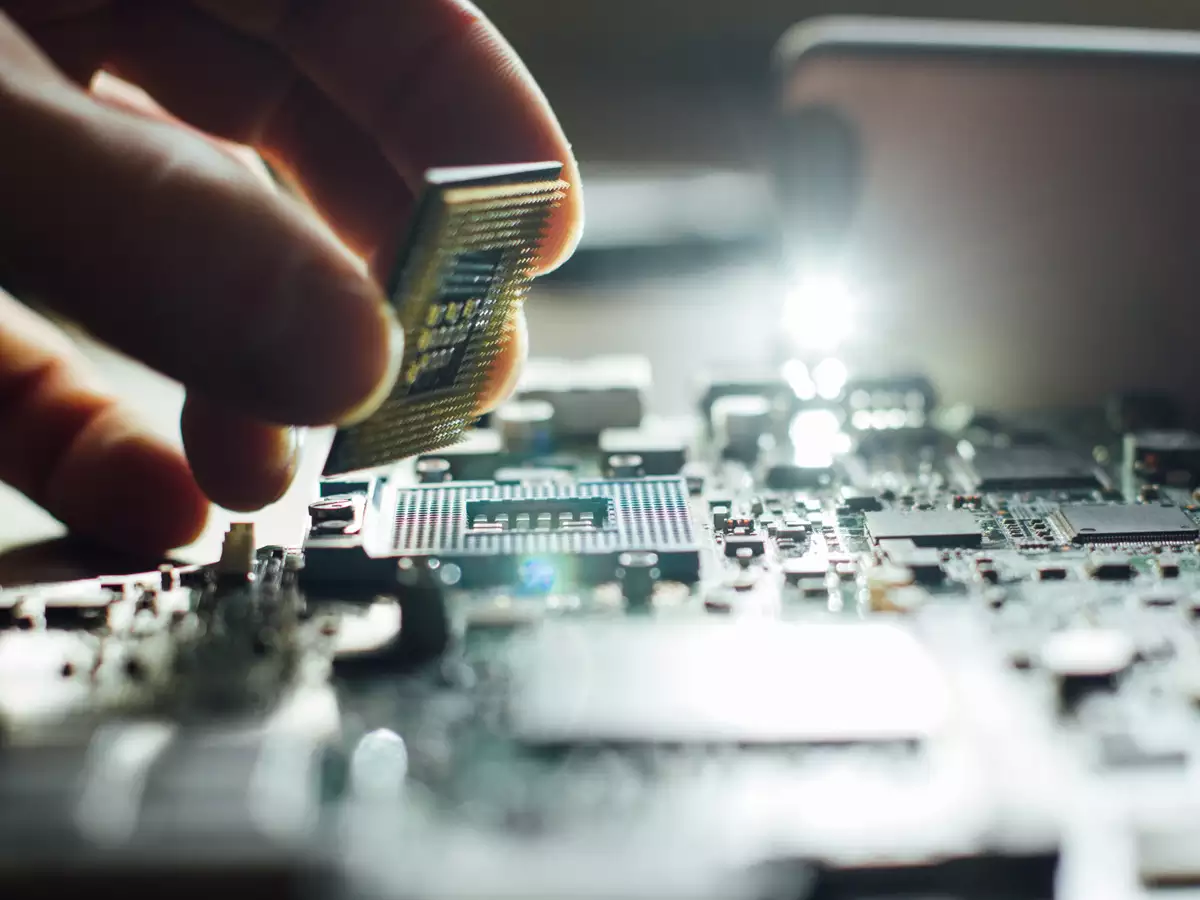

To comprehend President Joe Biden's challenge in taming a semiconductor shortage bedeviling automakers and other industries, look at a chip given by a U.S. firm for Hyundai Motor Co's new electric vehicle, the IONIQ 5.

Production of the chip, a camera image sensor created by On Semiconductor, commences at a factory in Italy, where raw silicon wafers are imprinted with complex circuitry.

The wafers are then sent first to Taiwan for packaging and testing, then to Singapore for storage, then to China for assembly right into a camera unit, and finally to a Hyundai component supplier in Korea before reaching Hyundai's auto factories.

A shortage of this image sensor has resulted in the idling of Hyundai Motor's plant in South Korea, so that it is the latest automaker to suffer from global supply woes that crippled production for the most part automakers including General Motors Co and Ford Motors Co and Volkswagen.

And the winding journey of the image sensor shows just how complicated it will be for the chip industry to both crank up capacity to address the existing shortage and re-invigorate U.S. chip manufacturing.

U.S. President Joe Biden on Monday convened semiconductor industry executives in Washington to go over solutions to the chip crisis, the most recent move in a broader effort to strengthen the domestic chip industry. He's also proposed $50 billion to aid chip manufacturing and research within his $2 trillion infrastructure proposal, which he said would help the United States win the global competition with China.

A lot of that money will likely go towards the construction of multi-billion-dollar advanced chip plants by Intel, Samsung and TSMC. But industry executives say addressing the broader supply chain is essential, and the Biden administration faces complicated choices which elements of it to subsidize.

“Trying to reconstruct a whole supply chain from upstream to downstream in a single given location just isn’t a chance," David Somo, senior vice president at ON Semiconductor, told Reuters. "It might be prohibitively expensive."

The United States now only makes up about about 12% of worldwide semiconductor manufacturing capacity, down from 37% in 1990. More than 80% of global chip production now happens in Asia, according to industry data.

1,000 STEPS, 70 BORDERS

Creating a single computer chip can involve more than 1,000 steps, 70 separate border crossings and a host of specialized companies, most of them in Asia and largely unknown to the general public.

The procedure starts with plate-size discs of raw silicon. At chip factories referred to as 'fabs,' circuits are etched in to the silicon and built up on its surface through some complicated chemical processes.

The next phase - packaging - offers an excellent illustration of the supply chain challenges.

Wafers emerge from fabs with hundreds as well as a large number of fingernail-sized chips on each disc. They need to be break up into individual chips and put into a package.

Traditionally that meant positioning each chip onto a “lead frame” and soldering it to a circuit board. The complete assembly would then be packaged in a resin case to safeguard it.

That process is quite labor intensive, leading chip companies to outsource it decades ago to countries including Taiwan, Malaysia, the Philippines and China.

The packaging step itself has its supply chain: South Korea's Haesung DS, for example, makes packaging pieces for automotive chips, exporting them to Malaysia or Thailand for customers including Infineon and NXP. These companies, or in some cases a sub-contractor, then assemble and package chips for automotive suppliers like Bosch and Continental, which supply final products to automakers.

“If they (the Biden administration) will be successful with this, they will need to help rebuild the package industry within america," said Dick Otte, CEO of Promex, a California-based chip packaging firm.

"Otherwise this is a waste of time. It really is like creating a car and not having a body to put up it."

But newer chip packaging processes are much less labor intensive, leading some U.S. chipmakers to believe they can be cut back from abroad.

In October, Minnesota-based chip foundry, SkyWater Technology took over a facility in Florida where it plans to build out advanced packaging lines.

“There's kind of an industry-wide agreement that all this must happen here,” Thomas Sonderman, leader, SkyWater Technology, said.

FASTER TURNAROUND

Rebuilding the U.S. packaging industry would not only insulate chip companies and their customers from political risk, it might also help them break free of the long cycles involved in creating new chips, said Tony Levi, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Southern California.

By doing more work locally, U.S. chip organizations could create smaller manufacturing runs of chips more often, speeding innovation and potentially creating the ability to more quickly adapt to demand.

Levi said that Arizona, Texas and New York - where Intel, TSMC, Samsung and GlobalFoundries all have existing or planned facilities - will be suitable for cluster supply chain elements like packaging.

“What the U.S. is very good at is close collaboration between system design, product design and the manufacturing itself,” Levi said.

Still, it remains to be observed the way the Biden Administration will balance the demands of the many sub-sectors of the chip industry.

Numerous firms, most of them overseas, provide critical foundry materials including wafers and gases. The complex tools used for advanced chip production are mostly manufactured in america, but that isn't the case for factory components like the robotic systems that whisk chips among the many process steps.

In addition, some in the industry argue that the U.S. must support not merely new cutting-edge fabs, but older technology too. It is the more mature chips that are in severe shortage, noted Tyson Tuttle, CEO of Austin-based silicon design firm, Silicon Labs.

"We've a mismatch of capital in the semiconductor industry," he said, with an excessive amount of the money going to the innovative technologies.

E. Jan Vardaman, President at TechSearch International Inc, said the chip packaging industry has been under extreme price pressure, resulting in smaller margins than chip factories and chip design firms. "From a financial and economics viewpoint, it does not seem sensible for them to make a major investment."

"Simply throwing money as of this does not solve the problem. This is a more technical problem."

Source: japantoday.com