Why West African art is on the rise: 'The awakening of a sleeping giant'

Over the past few years the number of African galleries circulating on the contemporary fair circuit has soared, with a growth in collectors both on the continent and internationally. Artists, who formerly left Africa for western art-world centres, are now suddenly remaining on the continent or even returning.

When Christie’s and Ghana’s Gallery 1957 held a show in Dubai last year they called it West African Renaissance – a nod to the centring of attention on the continent.

“The talent is here,” says Marwan Zakhem, who opened Gallery 1957 in 2016 after years of collecting and supporting artists. “It is the right time. Artists like Amoako Boafo are just the cherry on the cake. He is selling for $3.3 million – that’s just pouring flames on a fire that’s already burning.”

But the emergence of art fairs in Africa has allowed artists and galleries to make connections outside of their local boundaries. Art Joburg in South Africa launched in 2008; Investec Cape Town Art Fair in 2012; and ART X Lagos in 2016. In addition, 1-54, the fair devoted to African and African diaspora galleries, started in 2013, with an event in London, and has since expanded to events in Paris and Marrakesh.

The shift is from a number of local scenes to the international system of galleries and fairs.

“Before there weren't galleries, but there was art,” says Touria El Glaoui, who founded 1-54. “Collectors had personal relationships with artists and had been collecting them directly for years. Suddenly, we showed them a new model, where galleries were included and you had to have a gallery that represents you at the art fairs. Many of the collectors on the continent didn’t understand why you have to pay 50 per cent more of the price, which galleries needed not only to make a profit, but also to be part of the international art market. But now they’re starting to understand the good work the galleries are doing by including artists in museum shows and in international collections.”

New collector bases

The interest by international collectors is key. The racial awakening in the West around Black Lives Matter has pushed European and American galleries and museums to try and correct their disproportionately white stables of artists. Magazines are devoting more attention to black and African artists, and collectors are following suit.

“For me what changed between before Covid and this year is the great appreciation of African art,” says El Glaoui. “There were always the usual collectors coming to 1-54 as part of the Frieze Week circuit. But this year we were very instrumental. There was a lot of complaints that we didn't have enough work – because we had so many more collectors – and there were no complaints about the prices, which makes all the difference.”

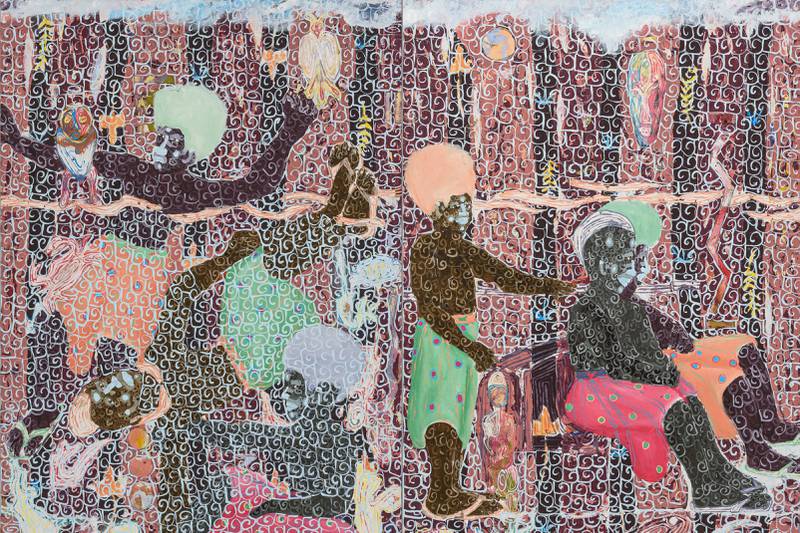

Many credit the rise in prices to one individual in particular: Amoako Boafo, the talented Ghanaian artist whose prices increased a hundredfold from 2018 to 2020, particularly after he was championed by the influential Rubell family of collectors. His story made for great copy: once working in Ghana to support his mother and sister, he is now seen alongside Paris Hilton, Joan Smalls and Karolina Kurkova at art parties held in his honour and at art fairs. A rush of collectors began flipping his works at auction, or buying them from his galleries and quickly putting them up for sale, where they fetch millions. Last December, an Asian buyer at a Christie’s Hong Kong auction set a record for a Boafo, paying $3.3 million for Hands Up (2018), a portrait of a woman in cat-eye sunglasses holding up her palms.

While Boafo has caught the attention of American collectors and those who follow the auctions, many on the continent say their collector base has also been steadily growing from buyers who are relatively new to the art market. These include African collectors who are now buying beyond their national countries, Chinese buyers, collectors from Arab countries, and, in particular, African-American buyers. The last group, many gallerists say, see African art as a way to connect with and support their roots – and, in some cases, they have been shut out of the established gallery system in the US.

“A class of collectors that has popped up is African-Americans who have made money in the past 20-30 years,” says Daudi Karungi, whose gallery Afriart is farther east, in Kampala, but who has become one of the new galleries participating at international fairs such as Art Basel Miami Beach and Abu Dhabi Art, as well as fairs across the continent. “I remember some of my collectors telling me that they were not being sold art by the white galleries in the US. I understand, because when you have a scarcity of art, how do you prioritise who to sell it to? In most cases you sell it to those you have relations with. It is understandable from a business point of view, but it is a gap that has pushed a lot of money into the acquisition of art from Africa.”