Trade deficit shrinks on low imports

Trade deficit narrowed down to 15 percent last fiscal year thanks to a decline in imports and steady growth of exports, bringing some breathing room for the government for the time being.

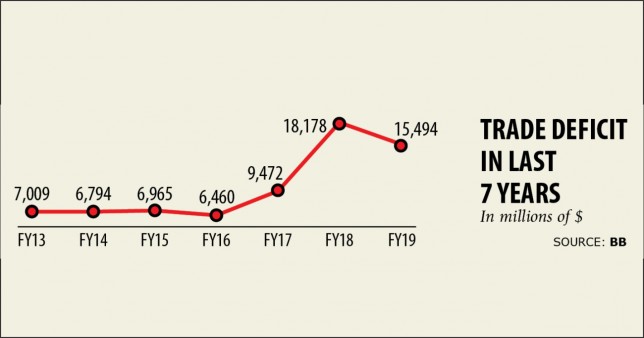

In fiscal 2018-19, trade deficit stood at $15.94 billion, down from $18.17 billion a year earlier, according to data from the central bank.

Despite the declining volume of the trade gap, this is the second largest ever deficit in Bangladesh’s history.

Imports stood at $55.43 billion last fiscal year, up 1.79 percent year-on-year, while merchandise exports rose 11.49 percent to $39.94 billion.

Low imports indicate that the country’s investment has been sluggish, said Fahmida Khatun, executive director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue.

The country’s private investment to GDP ratio has been hovering around the 23 percent-mark for the last couple of years, she said. But a hike in investment is urgent considering the needs of employment generation.

“One kind of political stability remains in the country. But this has failed to bring back the confidence of businesses.”

One of the reasons, she pointed out for the poor investment scenario is the country’s feeble infrastructure.

Exports are also heavily dependent on a single sector -- apparel -- which is a risk, according to the CPD executive director.

“We can advance a little by depending on just one sector. We should diversify exports to boost our economy and absorb shocks deriving from both external and internal areas,” she added.

About 90 percent of the imports entering the country are generally used in the productive sector, so the low trend of imports is an indication of stagnancy in private investment, said MA Taslim, an economics professor at the Independent University of Bangladesh.

He raised a question about the high GDP growth last fiscal year given the low imports, saying the growth might be lower than the actual one if the calculation method is followed accurately.

“A recent research revealed that the government of India had been showing higher GDP growth for several years than the actual one. The example may be the same in Bangladesh if such research is carried out here.”

He echoed the same as Khatun on overreliance on the garment sector as it may face a difficult situation if the workers’ skill are not improved, said Taslim, also a former chairman of the economics department of the University of Dhaka.

“Large or small trade deficit is not a matter of problem for a developing country like Bangladesh. The core concern is whether we can use our imported goods properly and diversify exports in order to increase the earnings.”

Many industrial items such as bicycle, leather and shipbuilding had earlier sparked huge potential but the government did not give adequate attention to the sectors.

“The government should revise both trade and export policies for the sake of the economy,” he added.

The lower trade gap has also helped lessen the deficit in the current account, but the sum is still sizable: it decreased 45 percent year-on-year to $5.25 billion last fiscal year.

“The current account enjoyed a surplus for a long period just three years ago. The deficit means the country managed the situation by way of taking loans from foreign sources,” Taslim said, adding that the situation is still manageable.

But in the long run, dark clouds will gather if the trend continues in the years ahead, he added.