Subcontracting loses out to compliance

A drought of fresh investment in opening small enterprises is sweeping across the garment sector, an outcome of stringent conditions set by retailers and brands for subcontracting parts of apparel production mainly to avert industrial accidents.

The once booming opportunities for subcontracting have nearly evaporated following the nation's deadliest back-to-back industrial disasters, the 2012 Tazreen Fashions fire and 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse.

“Subcontracting in the garment sector is not banned but a subcontracting factory must be very compliant,” said Siddiqur Rahman, president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), yesterday.

Subcontracting, a third party contract, becomes essential whenever there is an overflow of work orders in any factory. It also helps maintain shorter lead times set by international apparel buyers.

Now subcontracting is rarely allowed in garment factories because of the poor compliance records of the small units, Rahman said, adding that only when a buyer permits can a big factory subcontract its work orders.

Taking subcontracts have always been the initial stepping stones for new entrepreneurs trying their hand in the garment sector as such enterprises have low operational costs and require little capital.

No new subcontracting firm has been set up after the Rana Plaza building collapse. Only the big factories, which are highly compliant, can subcontract their work orders, albeit in their own sister concerns, Rahman said.

Anybody seeking to set up even a small factory and wanting to become a member of the BGMEA now needs to pass the association's rigorous audit and inspection, something which had been lax in the past.

“So, setting up any factory is now a tough task because of strong compliance requirements set by the buyers,” Rahman said.

After the Rana Plaza collapse, some 1,200 small and medium-sized factories were shut for failing to either achieve factory remediation or meet strong compliance requirements of buyers.

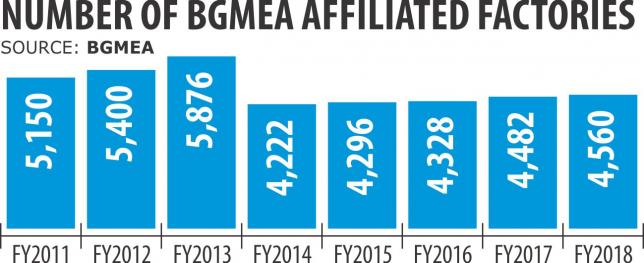

In the fiscal year of 2010-11, the number of active garment factories affiliated with the BGMEA stood at 5,150 and it reached 5,876 in 2012-13, according to the association's estimate.

But the number of factories, especially subcontracting ones, has begun to decline after the collapse, following which two foreign bodies, the Accord and the Alliance, started inspection and remediation.

In just a span of one year, the number of BGMEA members declined to 4,222. The number increased a bit in 2017-18 to 4,560 as owners of some big business groups reinvested and opened new complaint factories.

Ahsan H Mansur, executive director of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, said subcontracting has both positive and negative sides. On one hand, it helps reduce lead time and generates jobs for unskilled and semi-skilled workers as it comprise less complicated work, he said.

On the other, subcontracting factories had the habit of paying little to no emphasis on compliance, the prime aspect blamed for industrial disasters.

In absence of specific guidelines on subcontracting, only buyers dominate in setting up compliance rules and determine fates of subcontracting factories, Mansur said.

He said with subcontracting no longer ongoing on a massive scale, new entrepreneurs are not coming up and only big factory owners are undertaking expansion and reinvesting.

Subcontracting still occurs in Bangladesh but on a very limited scale, the expert said. As a result, factory owners are planning to subcontract work orders to some Sri Lankan factories.