'I'll never leave the stage'

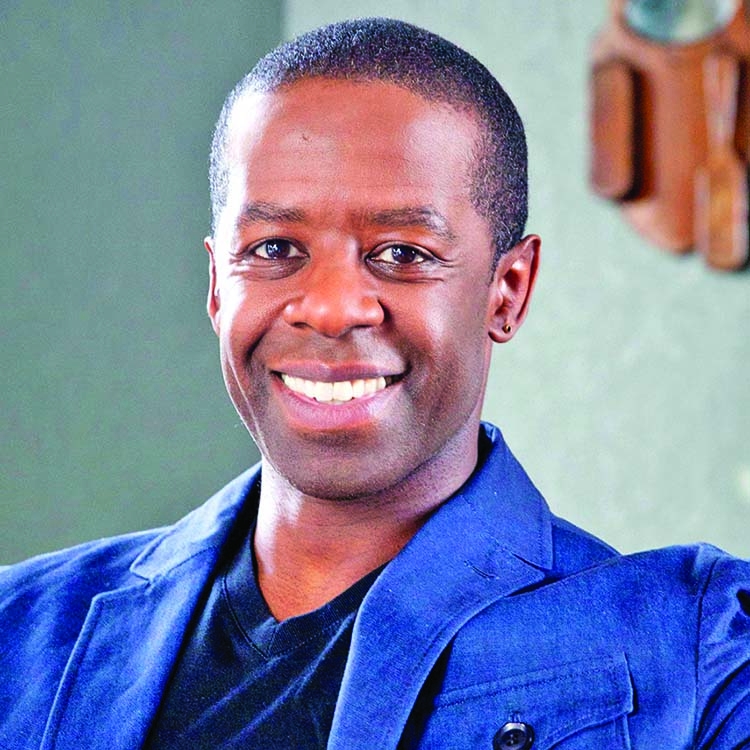

In the short and possibly quite nerve-racking break between an afternoon rehearsal and an evening preview, Adrian Lester is trying both to eat a sandwich and to find the right words to describe to me (via Zoom) what he and his co-star have been doing to their already much acclaimed production of Lolita Chakrabarti's play Hymn ahead of its long-delayed opening at the Almeida theatre in Islington. "

I suppose you could say that we've had to 'un-camera' it for the stage," he tells me, wiping what might be mayonnaise from the corner of his mouth. "But of course what we've really done is to go back to the original idea of it, because the play was written, and rehearsed, for a live audience. It was only when the first lockdown began and Rupert [Goold, the Almeida's artistic director] said that we were going to carry on with the production, no matter what, that we made the decision to film and live stream it."

If you were one of those who saw Hymn on screen last February, you may perhaps be wondering why any changes at all are required, even allowing for the fact that the rules are different now; the strict social distancing of Lester and his co-star, Danny Sapani, mirrored so powerfully the emotional distance between their characters. But perhaps this isn't important. In the end, what really matters - to Lester and Sapani, at least - is that this time around they will be able to see and hear their audience. "It was very strange last year," he says. "

Doing things we thought would be funny or touching with no physical audience." However much damage the pandemic has inflicted on the theatre, he can't help but think that it has also given us a renewed grasp of the role art plays in our lives. "After last night's preview, people said how moving it was to be alongside strangers after so much time apart, reacting to the same things at the same moment. We're pack animals. We've missed the collective experience. We need to be together."

Hymn is a play about the burgeoning friendship between two middle-aged men, Gil (Lester) and Benny (Sapani), a bond that springs up following their unexpected meeting at a funeral. It's funny and touching: together, they sing a cappella versions of soul classics and breakdance to Chic and the Temptations; Lester even plays the piano. But it's very far from being, as some of the reviews put it, a "bromance". Beneath the surface, both are struggling with feelings of inadequacy, a sense of failure they dare not quite identify out loud for fear of making it more real.

"To call it a bromance is just lazy," says Lester. "The play asks big questions. What does it take to be a good father or brother or son? How does a man deal with the fact that he has no sense of achievement? Each character has what the other one doesn't and thinks they're less of a person because of it."

It's also, he says, uniquely demanding to perform. "It's just the two of us and so much happens in only 90 minutes. At the curtain, the audience is applauding our virtuosity as much as they are the story. It really pushes us as actors. Timing, intellect, emotions, physicality: it tests all these things. By the time we get to the end, we're soaked in sweat."

Chakrabarti, who just happens to be Lester's wife, wrote Hymn with Lester and Sapani in mind. She had a hunch they'd make "the perfect match" and Lester thinks now that she was right: "We have this unconscious invisible thing on stage where we'll cover for each other," he says. Is it tough, working with her? Does she give him annoying notes? He laughs. "

No, it's great. We've been doing it for years. We met at drama school [they were at Rada in the late 1980s] and then we became parents [they have two daughters] and got a mortgage; everything has always bounced between us and this is just an extension of that, really. It's give and take. She's an actress, too, so she knows there are areas where I have to create on top of her words and she lets that happen. But equally, I'm not a writer and there are times when I just have to wait and see what I'm given."

They're both satisfyingly busy at the moment, pinging between projects like pinballs. In September, Lester will replace Ben Miles in the National Theatre's celebrated production of The Lehman Trilogy when it finally transfers to Broadway; in November, Chakrabarti's irresistible adaptation of Yann Martel's Booker prize-winning novel Life of Pi, first staged at the Crucible theatre in Sheffield in 2019, arrives in the West End.

But this is not to say they've been immune to the effects of the pandemic: "One job I was really looking forward to just disappeared because of the lockdown and suddenly I was unemployed." What does he make of the level of support that has been offered to the performing arts by the government? "There was a feeling that the way the industry worked wasn't understood by those in charge.

In terms of help, we seemed to be pretty far down the list. It has been very, very hard and even now we're not back to normal. Go through the West End - it's quite quiet." Does he worry about what might still be lost? "Yes. Some buildings have already gone - I can't name them now, but they're not going to reopen - and some people have had to find other jobs away from the theatre because they just couldn't sustain themselves."

He hopes fervently that there'll be no more lockdowns, not least because he is so excited about The Lehman Trilogy: "I've never done Broadway before." Sam Mendes, its director, first talked to him about appearing in it long before it opened in London. "I read the script early on, when it still had about 40 parts [in Ben Power's adaptation, three actors play every role]. But I had other things on and couldn't do it."

Isn't he a bit nervous about the idea of taking a play that's as much about New York as it is about a family business to New York? "It is like taking kilts to Scotland," he says. "But the three of us [his co-stars are Simon Russell Beale and Adam Godley] have gentle Bavarian accents in the play. We're a bunch of Europeans coming to New York, if I'm allowed to say that."

Lester has had a highly successful screen career. During lockdown, he starred in Mike Bartlett's much talked-about BBC One series Life, a (kind of) spin-off from the hit Dr Foster; some people will always remember him best for his role in the long-running Hustle. But it's still the stage that he finds most compelling. "I'll never leave it," he says. "

The intellectual and emotional power of the material has always been greater in the theatre for me; it's always a new conversation, because every audience is different. I know some actors don't want to see faces out there; they prefer to perform to a black wall. But I like knowing I'm talking to people. I look out and I find someone to perform for: that person at the back, I'll do it for him. It really helps, especially with darker material."

But the fact that he has had so much acclaim for his theatre work - as Henry V and as Othello; as Robert in Stephen Sondheim's Company, for which he won an Olivier award - has little or no effect, he insists, on his state of mind when it comes to the future. "It's like being on one of those moving walkways at an airport," he says. "

If you stop to think how nice everything is even for a moment, you're already going backwards again. You have to keep walking. I'm constantly worrying about what I'm going to do next." There is a pause and then he goes on. "When I stand back and look at people I was at drama school with, and think of how good they were, yes, I do have to pinch myself. I know I've been lucky.

But when I get an audition, I haven't got the job, I've only got the opportunity - and when I've got the job, there's a lot of hard work and bloody mindedness yet to come." Is this a prompt? For the first time in our conversation, he looks suddenly like a man who knows it will be curtain up in less than two hours' time. "I'll always be awake at three in the morning, going over my lines," he says, his hands reaching swiftly, and with some finality, for his earphones.