How one historian is using new technology to preserve India's ancient art

For decades, photographer and art historian Benoy K Behl has used his camera to illuminate dark, mysterious and even forgotten corners of ancient Indian history. He has a lifetime of experience documenting India’s rich artistic heritage, and in showcasing Buddhist art from around the world, including Thailand, Siberia and Uzbekistan.

He’s now set to elaborate on these experiences in December at the India Pavilion in Expo 2020 Dubai, in a talk titled Forgotten Tradition of Ancient Art, which touches on the first 700 years of the world’s Buddhist paintings.

Behl realised he had a passionate interest in photography, history and philosophy when he was in high school in 1970. The first documentary he made on 16 millimetre film was in 1976 – Delhi: The Disappearing City was about the lost monumental heritage of India's famous capital territory. Since then, he has produced almost 150 documentaries on Indian art and history.

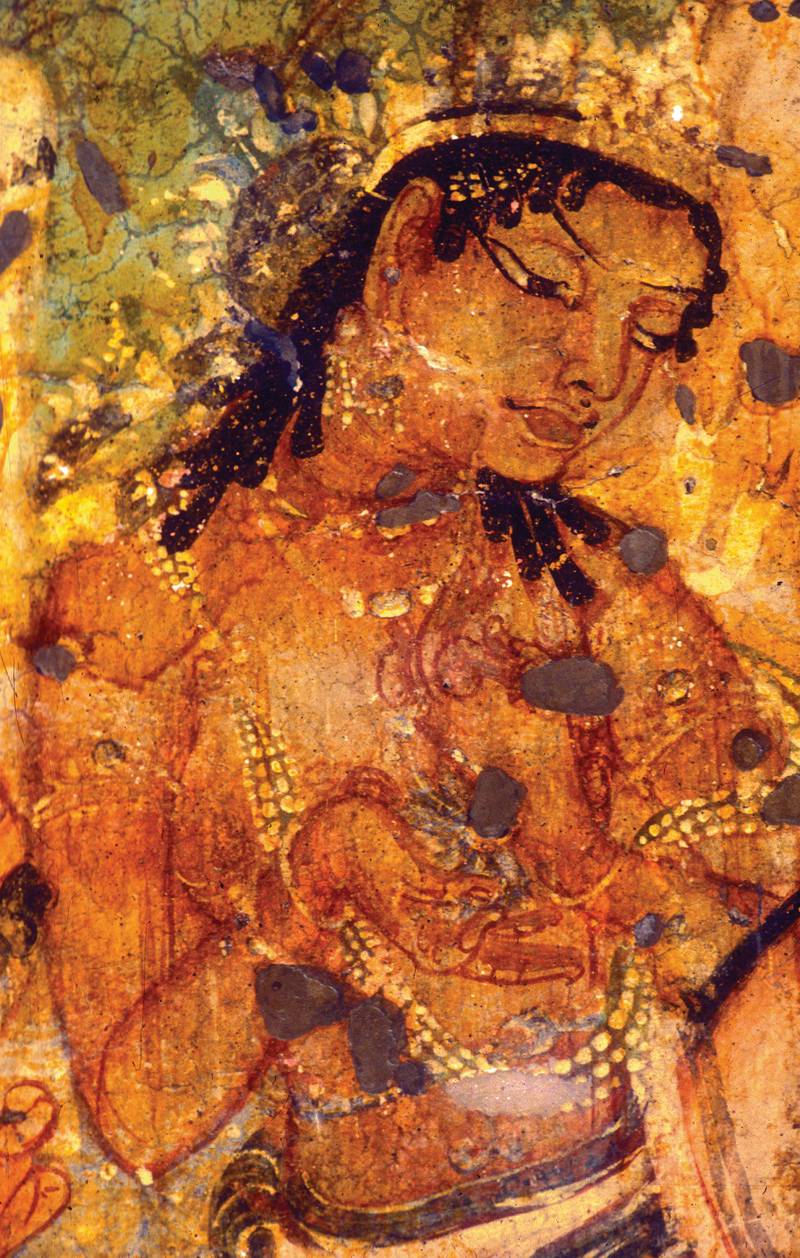

In 1991, Behl spent months capturing the rich colour and detail of India’s ancient Ajanta cave paintings, which he describes as the most revered in the Buddhist tradition. A Unesco World Heritage Site 100 kilometres north of the city of Aurangabad, the Ajanta Caves were once a retreat for Buddhist monks and the exquisite murals attracted 5,000 visitors a day pre-Covid-19. “These paintings were of immense importance to the world, but had never been clearly photographed before,” says Behl.

One of the challenging aspects of the project, Behl says, was that the photography could not involve the use of light. A flash from the camera could damage the delicate artwork dating back to 200 BC. He used long exposures to pick up natural, ambient light. The technique was lauded by art historians because it brought out rich colours that were hard to capture effectively on film and this lent a unique dimension to the artwork.

Behl’s mastery of low-light photography allowed him to effectively capture the paintings, but it meant long hours in pitch darkness, documenting every nuance of the murals. He emerged from the caves only for 10-minute breaks that punctuated these long hours of shooting. Later, he reconstructed the paintings digitally, in painstaking detail, over several months.

“The paintings of Ajanta changed my life,” Behl says. “I was overwhelmed, not just by the beauty and technical perfection, but by the grace, warmth and compassion that I saw in the images.”

The thousands of figures painted on the walls of the Ajanta Caves fascinated him. “These paintings taught me about kindness in a way which is far beyond that we can learn from any books or scriptures,” he says. “In fact, according to the Chitrasutra, the earliest known treatise on art-making, this is precisely the effect which great art is supposed to have. The aesthetic experience – when we respond to something truly beautiful – is a moment when the veils of illusion (maya or mithya) are lifted and we see the grace that underlies all creation,” he says.

Photographing the paintings kindled in him a desire to seek out the larger philosophy behind them and that sparked his travel to other Buddhist heritage sites around the world.

Two photographs that Behl has shot and restored of the Ajanta cave paintings have found their way to the Arctic World Archive (AWA), a for-profit project that began in 2017 in Norway. The AWA uses AI-driven nanotechnology to preserve digital data of historical and cultural interest from around the world. Fifteen countries have contributed so far. This data is buried in a steel vault, deep in a mountain in Norway. Among these digital records are manuscripts from the Vatican Library, masterpieces from Rembrandt and Munch, political histories and scientific breakthroughs.

In 2020, Behl’s restoration of a fifth-century painting that depicted Bodhisattva King Mahajanaka, who is believed to be an avatar of Buddha, was deposited in the AWA. “The painting captures the remarkable moment when the king rides out of the palace after renouncing all worldly pleasures,” says Behl. In May this year, a second painting titled Queen and Attendants, dating back to the sixth century, was sent to the archives, too. The painting depicts the queen as a regal figure waited on by her attendants, and is the oldest known form of Hindu art. The actual mural is located in the Badami cave temples in Karnataka.

The preservation of these two images is financed by Sapio Analytics, a tech advisory firm working with the government of India to assist in its efforts of restoring ancient heritage. “The images are now safe from cyberattacks. The digital film has a lasting life, even as the real-life monuments are heartbreakingly fragile,” says Behl.

Of the thousands of photographs on ancient Indian art and sculpture that he has photographed and documented, one of Behl’s favourites is the Padmanpani painting called The Bearer of the Lotus found in the first group of the Ajanta Caves. “Portraying peace and divine grace, this is a masterpiece in the world of art,” he says.

Behl’s work in Ajanta has had a wider impact in the art world. “Milo C Beach, director of the two American National Galleries of Asian Art [in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC], said to me that he would have to revise his understanding of the history of Indian paintings after studying my work,” he says.

“Ajanta’s paintings were somehow treated as a flash in the pan,” says Behl. “It was not seen or studied as part of a continuous tradition of art. However, since I was now showing him art of the 10th century, which had the same technical virtuosity as the fifth century Ajanta paintings, this pointed to the fact that there was a continuity and a great tradition of art.”

Behl went on to photograph other mural paintings of the ancient and medieval periods, and between 1993 and 2020, he has given talks in hundreds of cultural institutions, universities and museums around the world on the divine nature of the murals of India.

“My life has been spent as a labour of love, searching for the grace beyond the noise and turmoil of the material world. The ultimate purpose of art is to discover the peace and joy that can be found deep within us,” he says. This idea will power his presentations at Expo 2020. “I am looking forward to sharing this with as many people as possible in the days ahead.”