Hair-like cell structure may drive melanoma

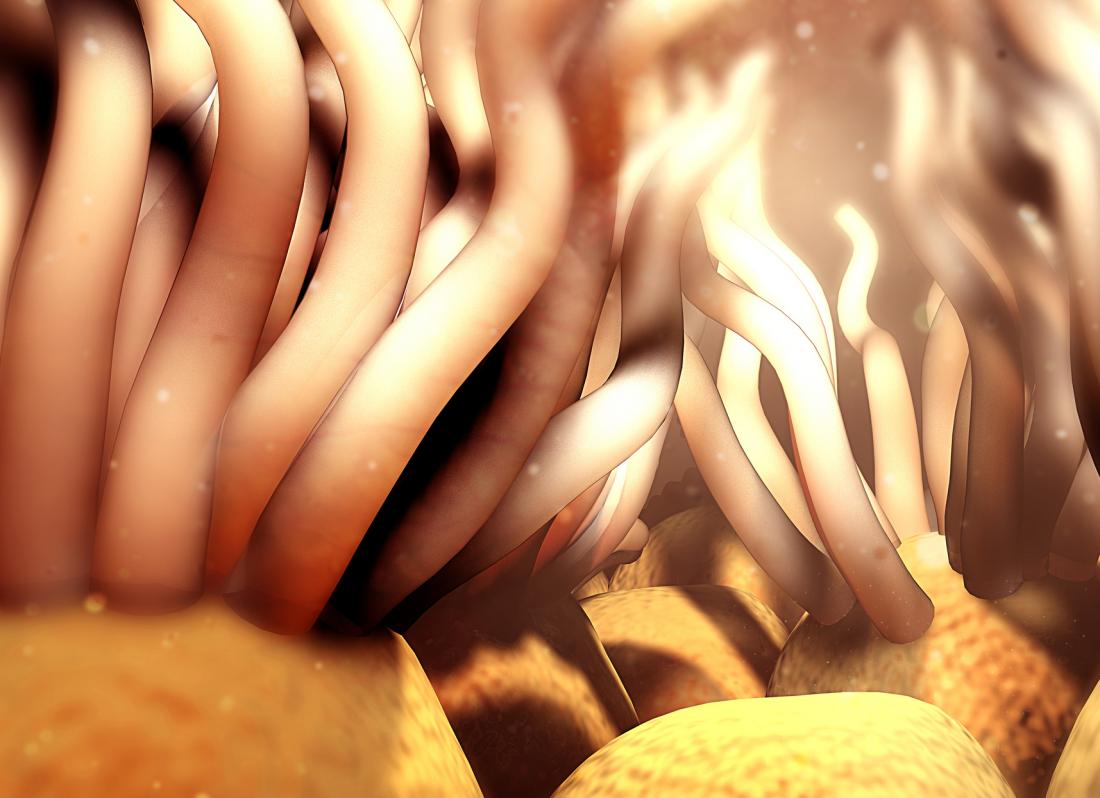

Cilia are hair-like projections that extend from cells' membranes. Researchers recently discovered that a lack of cilia may be linked to the progression of melanoma.

Skin cancer is the most common of all cancer types, and melanoma accounts for around 1 percent of diagnoses.

It is a particularly aggressive type of skin cancer affecting the cells that produce skin pigment.

Just this year in the United States, more than 90,000 individuals will be diagnosed with melanoma.

Although leaps and bounds have been made in the treatment of cancer in general, particularly in immunotherapies, there is still a lot of ground left to cover.

To close these gaps, it is vital to understand how different cancers survive and progress. Once we have a stronger understanding of the cellular mechanisms behind cancer cells' ability to thrive, we will have a better chance of interrupting them.

In this vein, researchers at the University of Zürich in Switzerland have recently been investigating the role of cilia in melanoma.

What are cilia?

Cilia are long, slender, hair-like projections found on nearly all of our cells. They are involved in a range of tasks, including cell proliferation, receiving sensory information, and communication between cells.

Although there are a number of diseases related to cilia — called ciliopathies — little is known about their role in cancer.

So, how did the researchers stumble across the potential involvement of cilia in melanoma? Initially, Prof. Lukas Sommer and his colleagues were looking at epigenetic factors that might be important in the progression of the disease. Their investigation was published recently in the journal Cancer Cell.

The genetic factors behind melanoma have been explored in some detail, but epigenetic changes are much less known. Although genetic causes are based on mutations in DNA, epigenetic causes are not; rather, they alter how efficiently a portion of DNA is translated into protein. The code stays the same, but the way it is read is altered.

In particular, the researchers were interested in a protein called EZH2, an enzyme that represses transcription. It is found much more commonly in melanoma cells than in healthy tissue.

So, the team started by studying all of the genes that EZH2 regulates, and what it found was intriguing.