Diabetes: Surprising new role of fat revealed

A new study, published in the journal Cell Metabolism, challenges the current understanding of what causes diabetes. The findings may lead to new therapies.

More than two decades ago, researchers suggested that the action of an enzyme called protein kinase C epsilon (PKC?) in the liver may cause diabetes. This enzyme, the researchers posited, inhibits the activity of insulin by acting on insulin receptors.

Since then, other studies have shown that knocking out the PKC? gene in mice protected the rodents from glucose intolerance and insulin resistance when they ate a high-fat diet.

However, the precise location where this enzyme activated remained unclear. Now, a new study — led by Carsten Schmitz-Peiffer, an associate professor at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Darlinghurst, Australia — suggests that the liver is not responsible for activating the enzyme and spreading its harmful effects. Instead, fat tissue throughout the body is the culprit.

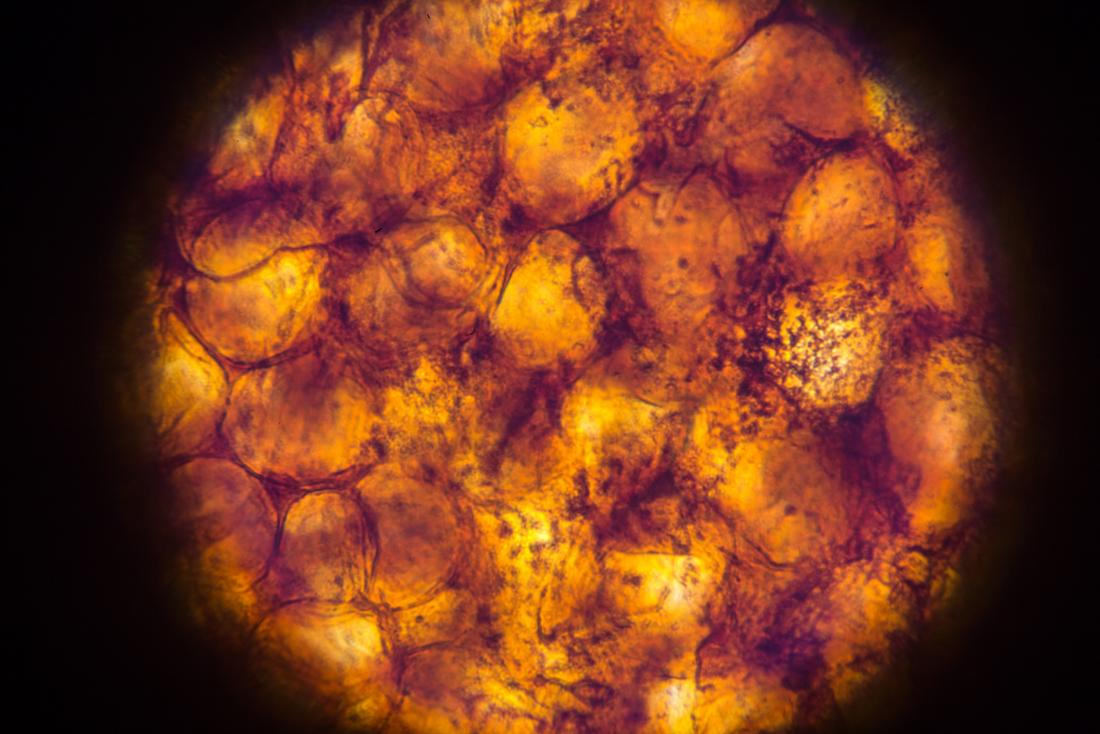

Obesity is a known risk factor for diabetes, and the current study adds to the mounting research that unravels the connection between body fat and the risk of developing the metabolic condition.

Additionally, the new study may lead to novel strategies of disrupting the activity of PKC?, ultimately leading to new treatments.

'Acting from fat tissue to worsen' diabetes

Schmitz-Peiffer and colleagues fed mice a high-fat diet, thus inducing symptoms of type 2 diabetes, such as glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, in the animals. Insulin resistance occurs when the liver no longer reacts to insulin, the hormone secreted by the pancreas.

Then, the researchers knocked out the gene responsible for PKC? in the liver, or the gene responsible for PKC? in the entire adipose tissue of the mice, and compared the results.

Schmitz-Peiffer reports on the findings, saying: "The big surprise was that when we removed PKC? production specifically in the liver — the mice were not protected."

"For over a decade," continues the lead author, "it's been assumed that PKC? is acting directly in the liver — by that logic, these mice should have been protected against diabetes."

"We were so surprised by this, that we thought we had developed our mice incorrectly. We confirmed the removal and tested it in several different ways, but they still become glucose intolerant when given a [high-fat diet]."