Confusion, seizure, strokes: How COVID-19 may affect the brain

A pattern is emerging among COVID-19 patients arriving at hospitals in New York: Beyond fever, cough and shortness of breath, some are deeply disoriented to the idea of being unsure of where they are or what year it really is.

At times this is linked to low oxygen levels within their blood, however in certain patients the confusion appears disproportionate to how their lungs are faring.

Jennifer Frontera, a neurologist at NYU Langone Brooklyn hospital seeing these patients, told AFP the findings were raising concerns about the impact of the coronavirus on the mind and nervous system.

By now, most of the people are aware of the respiratory hallmarks of the COVID-19 disease which has infected more than 2.2 million people around the world.

But more unusual signs are surfacing in new reports from the frontlines.

A report published in the Journal of the American Medical Association the other day found 36.4 percent of 214 Chinese patients had neurological symptoms which range from lack of smell and nerve pain, to seizures and strokes.

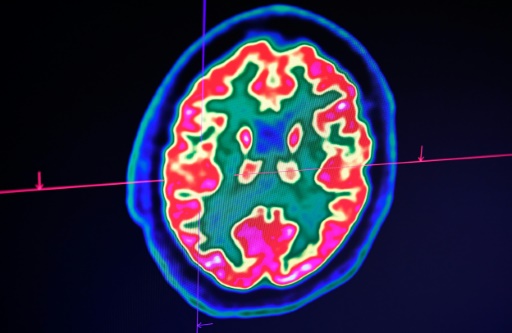

A paper in the New England Journal of Medicine last week examining 58 patients in Strasbourg, France discovered that over fifty percent were confused or agitated, with brain imaging suggesting inflammation.

"You've been hearing that is a breathing problem, but it also impacts what we most care about, the mind," S Andrew Josephson, chair of the neurology department at the University of California, San Francisco told AFP.

"In the event that you become confused, if you are having troubles thinking, those are reasons to get medical attention," he added. "The old mantra of 'Don't come in unless you're short of breath' probably doesn't apply anymore."

It isn't completely surprising to scientists that SARS-CoV-2 might impact the mind and nervous system, since this has been documented in other viruses, including HIV, which can cause cognitive decline if untreated.

Viruses affect the mind in one of two main ways, explained Michel Toledano, a neurologist at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

One is by triggering an abnormal immune response referred to as a cytokine storm that triggers inflammation of the mind -- called autoimmune encephalitis.

The second is direct infection of the mind, called viral encephalitis.

How might this happen?

The brain is protected by something called the blood-brain-barrier, which blocks foreign substances but could possibly be breached if compromised.

However, since lack of smell is a common symptom of the coronavirus, some have hypothesized the nose could possibly be the pathway to the brain.

This remains unproven -- and the idea is somewhat undermined by the actual fact that many patients experiencing anosmia don't go on to have serious neurological symptoms.

Regarding the novel coronavirus, doctors believe predicated on the existing evidence the neurological impacts are much more likely the result of overactive immune response instead of brain invasion.

To prove the latter even happens, the virus should be detected in cerebrospinal fluid.

It has been documented once, in a 24-year-old Japanese man whose case was published in the International Journal of Infectious Disease.

The person developed confusion and seizures, and imaging showed his brain was inflamed. But since this is actually the only known case so far, and the virus test hasn't yet been validated for spinal fluid, scientists remain cautious.

All this emphasizes the need for more research.

Frontera, who's also a professor at NYU School of Medicine, is part of a global collaborative research study to standardize data collection.

Her team is documenting striking cases including seizures in COVID-19 patients without prior history of the episodes, and "unique" new patterns of tiny brain hemorrhages.

One startling finding concerns the case of a man in his fifties whose white matter -- the parts of the brain that hook up brain cells to the other person -- was so severely damaged it "would basically render him in a state of profound brain damage," she said.

The doctors are stumped and want to tap his spinal fluid for an example.

Brain imaging and spinal taps are difficult to perform on patients on ventilators, and since most die, the entire extent of neurologic injury isn't yet known.

But neurologists are being called out for the minority of patients who survive being on a ventilator.

"We're seeing a lot of consults of patients presenting in confusional states," Rohan Arora, a neurologist at the Long Island Jewish Forest Hills hospital told AFP, saying that describes more than 40 percent of recovered virus patients.

It's not yet known whether the impairment is long term, and being in the ICU itself can be a disorienting experience because of this of factors including strong medications.

But time for normal is apparently taking longer than for individuals who suffer heart failure or stroke, added Arora.