At Bengal Classical Music Festival held in Dhaka, music signified much more than just clusters of seven notes

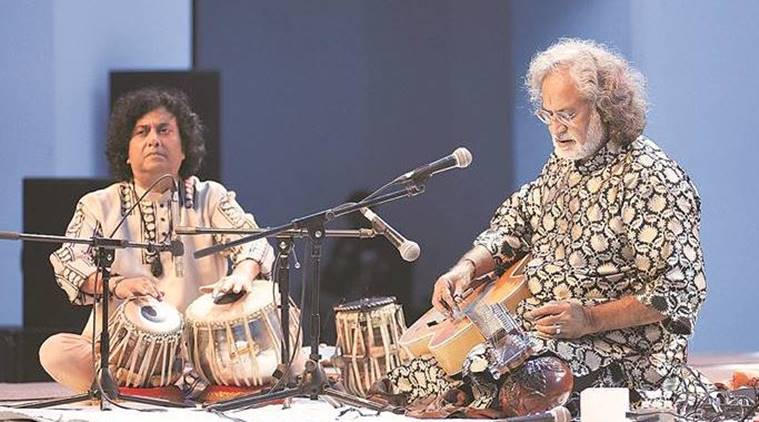

Pt Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (right) with Pt Subhen Chatterjee during his performance.

Dhaka's Bengal Classical Music Festival is not touted as merely a festival. As the country's culture minister believes, violence against minority communities can be tackled through the strength of music and that's the purpose of the all-night, five-day music festival that's free for all.

At about 1 am at Dhaka’s Abahoni Field in Dhanmondi, about 300 miles from Cox’s Bazaar on Teknaaf Highway where more than 8,30,000 Rohingya refugees are sheltering, Grammy-winning musician Pt Vishwa Mohan Bhatt was busy taming the notes of a cuckoo. At Bengal Foundation’s Bengal Classical Music Festival, the slides on his mohan veena (a modified Hawaiin guitar) replicated those of the bird that he heard in the morning after his arrival.

As he created echoes through his musical glides, the audience roared in applause. “I don’t understand classical music. But this is great fun,” said a sociology student from Dhaka University, while gorging on beef kebabs in the food court on one side of the stage, where large screens had been put up and he watched, fascinated.

Just after Bhatt’s recital was nearing conclusion with A Meeting by the River, the piece that got him the hallowed gramophone, he decided to croon a Bangla song, O re majhi re. The audience, about 40,000 of them, yelled and shrieked. In the context of classical music, this bit by a musician where he/she tries to make the audience feel involved and invested in a classical music concert by translating the complicated structures of the system into an easier order is considered quite populist. But when about thousands — children alongside their parents and grandparents, students with teachers, rich and poor, skull caps alongside monkey caps — sat listening to Indian classical music, and sang along in tune, even including the murkis Bhatt threw at them, the schmaltzy boat song seemed to have nothing with the poignant atmosphere that one felt.

On stage and in the festival grounds, people spoke of Pt Ravi Shankar, Ut Ali Akbar Khan, Ut Alauddin Khan as “our musicians” and Rabindranath Tagore as their “gurudev”. A couple of days earlier, the festival also observed a two-minute silence for losing “our own” Kishori tai (Kishori Amonkar) and Girija Devi. It was a moment that needed to be recorded.

That’s when it struck — here is a nation, dealing with much more than it can chew. The recent mob attacks on Hindu houses and temples in Nasirnagar (Brahmanbaria) and elsewhere in Gopalganj, Chittagong, and Sunamganj districts in Bangladesh, thousands of Santhals forced to flee the villages after two tribal Santhal Christians were killed. In the grim times, the festival came with a lilt in its step. Everyone was with everyone, enjoying classical music. “I don’t see any other way of making things better in the country. It is an all-night, five-day music festival, the entry to which is free. No one listening to music for 55 hours will pick the arms to kill; forget about killing their fellow countrymen,” said Abul Khair, Chairman of the Bengal Foundation. On the opening day of the festival, Asaduzzaman Noor, Minister of Cultural Affairs in Bangladesh had said, “This is not merely a festival. I believe that violence against minority communities can be tackled through the strength of music”.

So one saw, the choicest of the Jamdanis and colorful kurtas, lots of music and camaraderie among thousands at a classical music festival. Where the chairs were full, people brought out jute chatais and bedsheets and sat on them, eyes closed, listening. The performances included concerts by dhrupad maestro Pt Uday Bhawalkar, sitar players Ut Shahid Parvez Khan and Pt Buddhaditya Mukherjee, vocalist Pt Ajoy Chakrabarty, Pt Jasraj and flute exponent Pt Hari Prasad Chaurasia among many others.

The reverence Indian music found in Dhaka, was something one sometimes doesn’t even see back home in India. Our own all-night concerts, including the recent one held at Delhi’s IGNCA by SPICMACAY saw very few people towards the far end. As an Indian journalist in Dhaka, it felt that our cultural affinity and shared history melded together so organically. There was music, food, and a cackle of laughter. Everyone seemed happy here.

The festival was also a distant reminder of June of 1971, a couple of months after the declaration of the state of Bangladesh, when Pt Ravi Shankar decided to do “Concert for Bangladesh”. He’d brought on board sarod legend and brother-in-law Ut Ali Akbar Khan, his friend, student and ex- Beatle George Harrison, who then brought in some of his buddies — Bob Dylan, Ringo Starr, Eric Clapton and Leon Russell — to pick up their musical instruments at Madison Square Garden so that relief could be given to the 100,000 refugees pouring into West Bengal from East Pakistan (Bangladesh).

It was back then a wake-up call for the world, that had no idea of the genocide that had rattled the region and Shekh Mujib ur Rahman’s revolution for the liberation of Bangladesh. The two concerts were then attended by a total of 40,000 people and raised close to 2,50,000 dollars for Bangladesh relief. The world noticed. These were times when music worked as counterculture when it could change attitudes of people. Concerns of musicians were taken seriously by people. “It still hasn’t changed. I will not underestimate the power of music even now,” says Luva Nahid Choudhury, the curator of the Festival. She added that soon there will be a museum in Dhaka dedicated to artists and art of Bengal (East and West).

The sprawling traffic jams of Dhaka speak of its patience. The music festival spoke of a broad-minded, secular side of a nation, something people needed — a musical equilibrium. “Thank you,” said an elderly lady in the queue outside the cleanest mobile toilets we had seen at a music festival. “For what,” I asked. “For visiting. And for earlier.” On my walk back, it struck me, earlier meant 1971. When I looked back, she had melded into the clusters of people listening in rapt attention to the seven notes, which in those moments, signified music; and much more.