Four decades on, where's the HIV vaccine?

In the four decades because the first cases of what would come to be known as AIDS were documented, scientists have made huge strides in HIV treatment, transforming that which was once a death sentence to a manageable condition.

What we still don't have is a vaccine that could train human immune systems to ward off the infection before it ever takes root.

Here's the state of play on a few of these efforts, which authorities see as the "ultimate goal" in the fight to eradicate a virus that 38 million persons live with globally.

Why do we need a vaccine?

More people than ever now have access to medications called antiretroviral remedy or ART, which when taken as prescribed, keeps down the quantity of virus in their body.

This keeps them healthy and struggling to transmit HIV with their partners.

Beyond ART, persons at risky for infection is now able to get pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a pill taken every day that reduces the chance of infection by 99 percent.

"But access to medication is not organized in every part of the world," Hanneke Schuitemaker, global head of viral vaccine discovery at Johnson & Johnson's Janssen Vaccines, told AFP.

Even within wealthy countries, wide socio-economic and racial disparities exist in accessing these medicines, and vaccines have historically been the very best tools to eliminate infectious diseases.

J&J is currently carrying out two human efficacy trials because of its HIV vaccine candidate, and initial results from one of them may come as soon as "the end of this year," Schuitemaker said.

Why is it so challenging?

Vaccines against COVID-19 were developed in record time and also have shown remarkable degrees of safety and efficacy, helping lower caseloads in the countries luckily enough to have wide access.

A number of these shots were developed using technologies which were previously being used on HIV -- why haven't we'd breakthroughs yet?

"The human disease fighting capability doesn't self cure HIV, whereas what was clear was the human immune system was quite with the capacity of self curing COVID-19," Larry Corey, principal investigator of HVTN, a global organization funding HIV vaccine development, told AFP.

COVID vaccines work by eliciting antibodies that bind to the virus' spike protein and prevent it from infecting human cells.

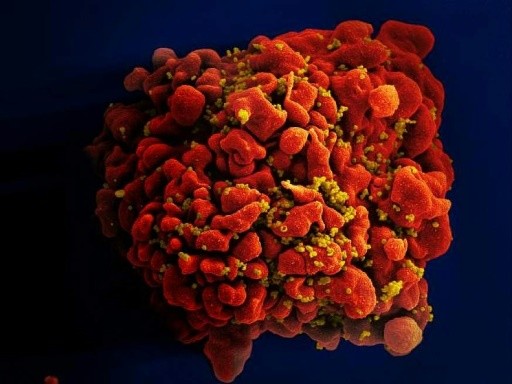

HIV also has spike-shaped proteins on its surface, which will be the target of HIV vaccine development.

But while COVID has tens of well known variants circulating worldwide, HIV has hundreds or thousands of variants inside each infected person, William Schief, an immunologist leading development of an mRNA HIV vaccine at Scripps Research Institute told AFP.

Because it's a "retrovirus" it quickly incorporates itself into its host's DNA. An effective vaccine should stop the infection dead in its tracks, not simply decrease the amount of virus and leave the remainder to stay with the person forever.

Where do things stand now?

Efforts to develop a vaccine have already been going on for many years but have up to now all ended in failure.

Last year, a report called Uhambo that was occurring in South Africa and involved the only vaccine candidate ever shown to provide some protection against the virus frustratingly ended in failure.

J&J's vaccine candidate is currently being trialed in 2,600 women in sub-Saharan Africa in the Imbokodo trial, which is expected to report results in the coming months.

It's also being tested in around 3,800 men who've sex with men and transgender individuals over the US, South America and Europe in the Mosaico trial.

The J&J vaccine uses similar adenovirus technology to its COVID-19 vaccine, basically a genetically modified cold virus gives genetic cargo carrying instructions for the host to build up "mosaic immunogens" -- molecules with the capacity of inducing an immune response to a multitude of HIV strains.

That is followed up by directly injecting synthetic proteins in later doses.

Another promising approach is to attempt to generate "broadly neutralizing antibodies" (bnAbs) which bind to regions of the HIV virus that are common across its many variants.

The International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and Scripps Research recently announced results from an early stage trial showing their mRNA vaccine candidate, developed with Moderna, stimulated the production of rare immune cells that induce bnAbs.

Their strategy, explained Schief, is to use a sequence of shots to attempt to gradually educate antibody making B-cells. They also desire to train up another sort of white cell, referred to as T-cells, to kill any cells that still get badly infected despite the antibodies.

Efficacy trials are still a far cry, but he's hopeful the mRNA technology, which turn your body's cells into vaccine factories and has tested its worth against COVID-19, can make the difference.

Source: japantoday.com